InQueery Symposium speakers discuss intersectionality in feminism

One speaker says abolitionist feminism can influence social movement conversations

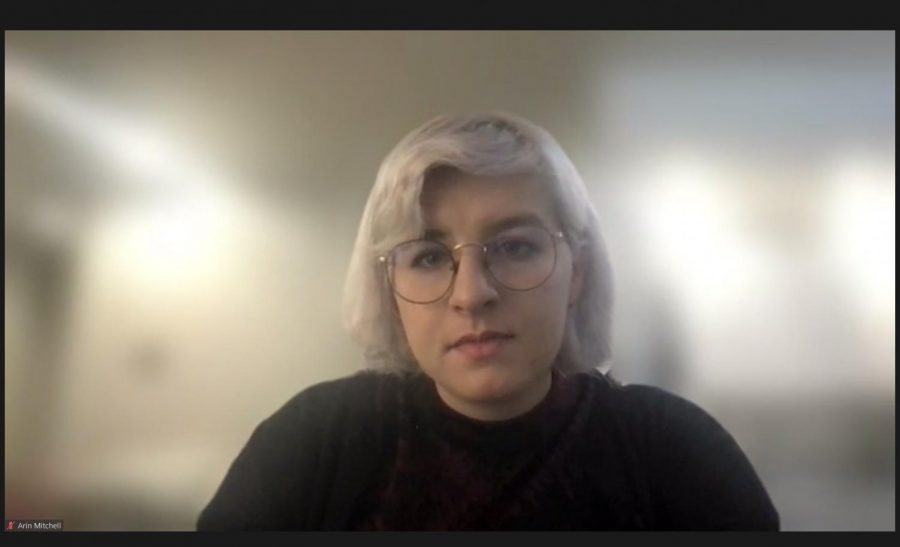

Arin Mitchell, second-year doctoral student in the College of Arts and Sciences, discussed how the theory of desserts is problematic.

November 17, 2021

A guest speaker and a WSU doctoral student spoke Tuesday night about feminism and oppression during the fourth annual InQueery Symposium hosted by the WSU Gender Identity/Expression and Sexual Orientation Resource Center; Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program; and the Women*s Center.

The organizations brought in Emily Thuma, assistant professor of U.S. politics and law at the University of Washington, Tacoma, as their keynote speaker to discuss abolitionist feminism.

Thuma said her presentation titled “The Queer Politics of Abolitionist Feminism” is based on research she conducted while writing her book “All Our Trials.” The book is about grassroots feminists, as well as the politics of violence, safety, criminalization and punishment in the 1970s.

Abolitionist feminism, which is mentioned in Thuma’s book, started off on the inside and outside of these prisons and was shaped through prison newsletters, she said.

“Specifically, newsletters that were edited and distributed by outside activists and that featured writings by imprisoned people,” Thuma said. “This is what I mean by inside and outside.”

There were multiple inside and outside prison newsletters in the 1970s, but there were only two that focused on women’s in-prison writings, she said.

One newsletter is called “Through the Looking Glass” and was based out of Seattle; the other is “No More Cages” and was based out of Brooklyn, New York, Thuma said.

“In their time, these two publications functioned as a really important space for a racially and economically and geographically diverse cross-section of incarcerated activists and their allies,” she said.

These two publications helped influence social movement conversations and helped the anti-racist and queer feminist politics move forward in a positive way, she said. The publications now offer a window to a world of anti-racist, queer, feminist resistance.

Along with Thuma’s discussion of newsletters in the 1970s, the InQueery Symposium held panels to discuss similar subjects.

Arin Mitchell, second-year doctoral student in the College of Arts and Sciences, discussed how the theory of desserts is problematic. The theory argues a subject deserves treatment as a result of an action, such as a student receiving a good grade on an assignment because they met all the criteria.

Mitchell said the base determines what the treatment should be. If a student does not meet all the criteria in this scenario, the theory suggests they receive something bad or a lack of something good.

“Very quickly, you can see that determining the relationship between what someone gets … and the reason for that can be pretty subjective,” she said.

Mitchell said what appears to be logical reasoning for what someone deserves is highly influenced by their social location, personal values and beliefs.

“Although these may appear objective, they’re actually incredibly subjective and typically are framed and created by those who dominate society,” Mitchell said.

The dessert theory is typically used to justify oppression or victim blaming, she said.

Mitchell said in cases of sexual assault, people tend to ask questions like what the victim was wearing, if they were dressed provocatively and whether they were drinking.

“In reality, these are incredibly unjust,” she said. “Nobody can truly deserve that kind of treatment.”

She said there are five forms of oppression: exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism and violence. Each form of oppression is supported by the dessert theory. Socially speaking, one group will have more power over another.

“As a result, we create this determination about how this one group at the top of the hierarchy deserves to have all of this money, power and prestige because of some characteristic, and those at the bottom do not deserve those types of benefits,” she said.

Editor’s Note: This article was edited to remove a quote misattributed to one of the speakers.