Asexuality and me, a reporter for the Evergreen

An asexual WSU student on being ace on campus

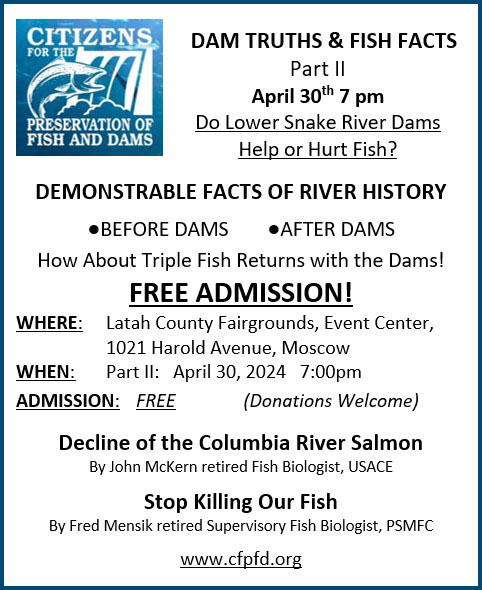

The asexual flag; the black symbolizes asexuality, the gray demisexuality and graysexuality, the white allosexual partners and allies and the purple community.

November 17, 2022

I couldn’t care less about sex.

Frankly, I never have. When I was younger, I thought people were joking when they said they thought someone was “hot,” or wanted to have sex with someone. Eventually, when I entered high school and my friends began to tell me stories of their sexual exploits, I realized that this wasn’t the case.

Even now, years after discovering I was asexual (specifically, a sex-indifferent asexual), part of me still thinks people are joking.

That isn’t to say I’ve never had a crush. I was quite the opposite, actually. “Boy crazy,” some might say. Contrary to popular belief, not all asexual people are aromantic; some, like myself, want relationships too. Romantic or aromantic, asexual, demisexual or graysexual, sex-indifferent, repulsed or positive, we are here. We exist.

However, a problem presents itself when romantic asexuals like me try our hands at dating.

Asexuality is one of the least known or understood identities in the queer community. So perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised when the first guy I was interested in at WSU told me he didn’t know what asexuality was after I came out to him.

Needless to say, having to explain to him my complete lack of interest in sex kind of killed the vibe.

To be clear, I hold nothing against the guy. Though he should’ve reacted more open-mindedly, I appreciate his desire to learn. Sure, it resulted in an unwanted and thus uncomfortable conversation about my sexuality, but that wasn’t my main issue with it.

Many asexual people face rejection from friends and family for being who they are and, like that conversation, it is rooted in ignorance. We are told that we’re broken, that it’s just a phase and that we just need to meet “the right person,” none of which are true. Even if we don’t hear that from our loved ones, we may hear it from strangers at work, online, or, in my case, at school.

It’s hard to want to date anyone at WSU when the best reaction I expect is complete unawareness and the worst is a dismissal of an entire aspect of my identity.

This is to say nothing about how many asexual people are pressured into sex by allosexual (people who do not identify as asexual) people who think we need to be “fixed” which, again, we don’t.

And in a university environment, where almost one in six students report experiencing nonconsensual sexual contact according to a 2019 Association of American Universities survey, a conversation about my asexuality with the wrong person could turn from unwanted and uncomfortable to unsafe, very quickly.

I’m lucky to have not gone through that, but what if one day I’m not so lucky? What about my fellow folks on the asexual spectrum?

All things considered, my asexual experience as a university student has, among other things, left me feeling a little isolated. I still don’t understand what makes someone “hot” or what makes sex so special, and I don’t care to understand. And that’s valid. But feeling like I can’t always tell people, crush or not, about this part of me can be alienating.

But I am who I am. And I want asexual people to know that they will find people who will accept them for who they are too, without any compromise. As I have, even here at WSU.