Bill addresses murdered, missing Native women

Legislation to increase collaboration for state, federal, tribal authorities

JOSEPH GARDNER | THE DAILY EVERGREEN

Kyra Antone, resident of the Native American Women’s Association and member of the Coeur d’Alene and Tohono O’odham tribes, discusses the disproportionate murder, abuse and kidnapping Native communities experience Thursday in the Native Center in Cleveland Hall.

February 25, 2019

A state senator re-introduced a bill that aims to help increase communication between federal, local, state and tribal authorities to address the violence against Indigenous women.

Congressmember Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), said the bill, “Savanna’s Act” will push for a more collaborative effort to ensure federal, state and tribal authorities work together to focus on high murder and kidnapping rates of Native American women.

The third-highest cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native women is murder, according to a report by the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI).

The Native American Women’s Association’s (NAWA) president and vice president spoke about the high rates of murdered and missing Indigenous women (MMIW) in Washington state and federal laws.

Kyra Antone, president of NAWA and a member of the Coeur D’Alene and Tohono O’odham tribes, said there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women in 2016, and the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System had only logged 116 of those cases.

“There’s just a huge gap in the information that’s there and that people are willing to go out and find,” Antone said. “I don’t think that it’s a big issue to other people.”

NAWA President Kyra Antone said there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women.

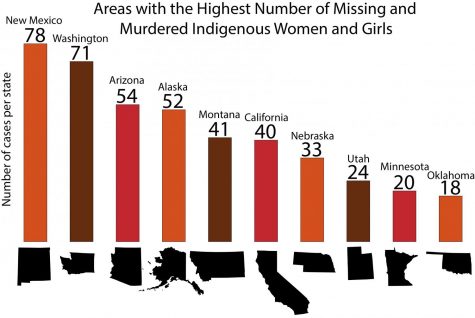

Washington state has 71 cases of MMIW, according to the UIHI report. The Pacific Northwest is one of the regions in the country with the highest number of cases.

MyKel Johnson, vice president of NAWA and a member of the Nez Perce Tribe, said there are stories and accounts of human trafficking in cities such as Seattle and Tacoma.

“It’s so surreal to us to live with that and understand that,” she said. “In our communities, we … know someone who has dealt with violence in their life, who is missing or who has died traumatically.”

Johnson said there are advocates and allies that will support indigenous communities.

“Then again, there are some people who go through life without ever recognizing our stories or our narrative,” she said.

Johnson said other than news outlets like Indian Country Today, media rarely addresses MMIW unless activists host a march or sit-in.

“Holding not only lawmakers accountable, but the system itself accountable to indigenous women to maintain and collect data, I think is really important,” she said.

There needs to be a better relationship in terms of tribal liaisons within those legislative bodies, Johnson said.

Antone said Washington state passed a bill last year to address the issue of MMIW. Outside of that piece of legislation, state lawmakers have not done much. There is nothing that gathers data concerning MMIW, she said. This is why Annita Lucchesi, who received her master’s from WSU, created a database for MMIW.

“As a native woman, it just feels like nobody cares,” Antone said. “Native people are often forgotten.”

She said despite the fact that tribes are sovereign nations, they have little jurisdiction over murders, rapes or kidnappings committed by non-natives because such cases are taken care of by the federal government.

The fear of being murdered or missing is prevalent in these communities, Johnson said, especially among young girls.

Even in Pullman, in the middle of a wheat field, it is scary to think about all the stories and the things that happen to indigenous women, she said.

“ ‘What if one day that’s me?’ How do you react to that? How do you go about your day? It’s no longer just school, work [and] social life,” Johnson said.

She said NAWA has held presentations regarding MMIW issues, as well as talking circles where people can discuss concerns in a safe space. Johnson said she knows of a girl from one of their communities who went missing, and is still missing.

Some tribes hold fundraisers, conduct research or work to bring awareness to the media about the missing girls, she said. They also hold MMIW events or marches to draw attention to this issue.

“They’re continuing to push that and bring it to the forefront and say, ‘This is happening. We are still here, and this is what we live with every day,’ ” Johnson said.

She said NAWA hosts an annual MMIW event in April to bring awareness to the issue.

The REDress Project focuses specifically on bringing attention to the issue. Last year, they hung red dresses off the bridge near Cleveland Hall, each one representing a missing or murdered Native women.

The event is not only to spread awareness, but to come together as women and empower one another, Johnson said.

Antone said these cases should be taken more seriously because they are often dismissed, which is frustrating, so a lot of women have taken it upon themselves to do something.

“This is our story, and it’s sometimes more real than we want it to be,” Johnson said.

WilLiam L. Burnes • Feb 28, 2019 at 10:17 am

Citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, living in Michigan. How can I help.

Wil

Sandra • Feb 25, 2019 at 10:48 am

This is awesome keep up the great work!!!