Resident tackles food insecurity

Moscow group compiled resource guide that includes food banks, pantries

OLIVER MCKENNA | DAILY EVERGREEN ILLUSTRATION

“Somebody receiving help, in my opinion, shouldn’t be made to feel like they need to go to the backdoor,” said Michelle Mason, chair of Poverty on the Palouse. The group focuses on food insecurity in the area.

November 5, 2019

Michelle Mason took a job as a waitress at IHOP in 2002 because she knew she just had to.

“I took it because I haven’t eaten for three days,” Mason, 46, said.

She asked the manager when was the soonest time she could begin her shift. She started working 30 minutes after she walked through the door that had a “Now Hiring” sign, she said.

“I got to eat that day,” she said. “I ate a lot of pancakes.”

Mason, who is also the chair of Poverty on the Palouse, said people who are food insecure may look for jobs that involve food.

“Working and food insecurity are not oppositional,” she said.

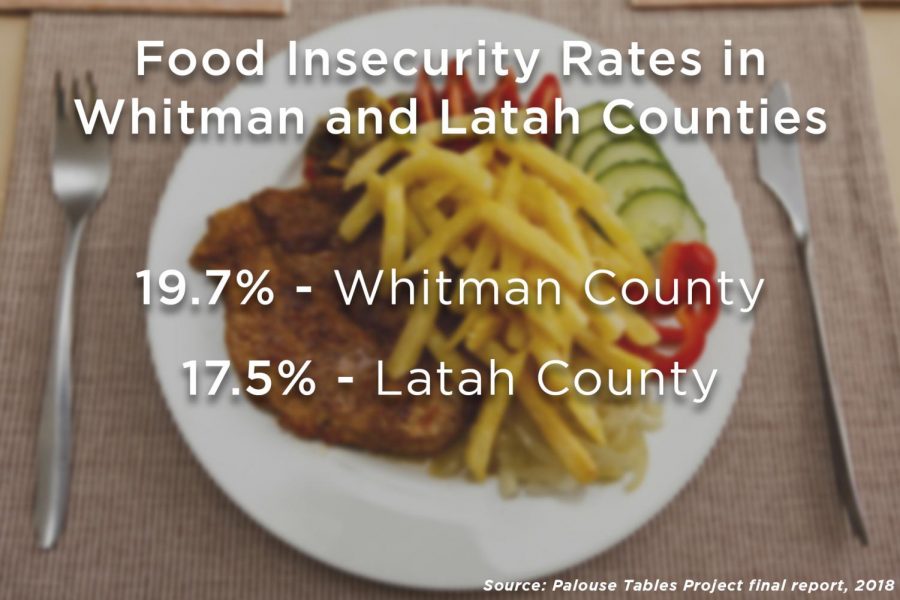

The food insecurity rate in Whitman County is 19.7 percent and 17.5 percent in Latah County, according to a 2018 report from the Palouse Tables Project.

Poverty on the Palouse is a group based in Moscow, Idaho, that focuses on food insecurity issues in both Latah and Whitman counties. Mason said the group works with local non-profit organizations like food banks and pantries.

Poverty on the Palouse has recently compiled a resource guide that includes not only food bank services, but also clothing and transportation services in Idaho and Washington. Additionally, the guide includes a list of programs that provide holiday baskets and dinners for those in need.

Two of the groups listed in the resource guide include Food Not Bombs of the Palouse and Rosario’s Place.

Henri Sivula, co-founder of Food Not Bombs of the Palouse, said they provide a community meal every Sunday in the basement of First Presbyterian Church in Moscow. The group has fed over 10,000 people after starting the group in April 2018.

Women*s Center director Amy Sharp said Rosario’s Place not only has non-perishable items, but also children’s clothing and diapers. WSU students visit Rosario’s Place at least once, if not multiple times a day.

As winter approaches, she said one of the smaller projects Poverty on the Palouse is working on is “suspended coffees”, which would give customers at a cafe an option to pay for an extra cup of coffee that a person in need could claim.

Mason said she has been food insecure her whole life. She still visits food banks until this day, and how often she uses it varies depending on the month. She usually gets a Thanksgiving basket around this time of year.

Mason said the first time she attended a Poverty on the Palouse meeting was in February 2018. She said he had wondered how many people in poverty were a part of the discussion.

“When I got there,” she said, “[it seemed] I was the only one in the room.”

One of the things she brought up with the group were issues with transportation services in Moscow. Mason said people who need food the most live in mobile homes, and mobile homes were not a part of the bus route at that time.

Not a lot of people in the room were aware of that, she said.

The bus used to not run on Saturdays, Mason said, which is the same day as the Moscow Farmers Market. One of the groups present at the market was Backyard Harvest, and they usually accept food stamps. A lot of people could have benefitted from it if the buses operated at that time, she said.

“None of them had realized that, because they never lived in a world where transportation was an issue,” Mason said.

SmartTransit updated its new service hours in August 2018, and the bus also started operating on Saturdays.

Mason said one of the biggest misconceptions about people in poverty is that they do not want to do better or that they take money out of the pockets of people who are working.

“There seems to be a wall — a shaming wall,” she said. “I wish that would go away.”

Sivula said although Food Not Bombs of the Palouse has a lot of volunteers who get the day-to-day operations done, it does not necessarily fight the systemic challenges surrounding food insecurity.

They said one of the biggest stigmas for marginalized groups — including those who are food insecure — is that they deserve to be treated poorly.

“It’s a f*cking bite to eat,” Sivula said. “If we can’t even start there, how are we gonna do anything else?”

Mason said there should be pride in getting support.

“Somebody receiving help, in my opinion, shouldn’t be made to feel like they need to go to the backdoor,” she said.

Anne Remaley • Nov 6, 2019 at 6:00 am

Thanks to The Evergreen for continually highlighting the critical issues we need to address. Articles such as this, that combine

narrative story with fact (stas on poverty, info on resources) are extremely effective in increasing our understanding and response to one another. I am continually heartened by your comprehensive, in-depth, and fearless reporting.