WSU team designs masks, tests level of protection for use

Masks to serve as last resort for healthcare professionals if shortage of protective equipment occurs during pandemic

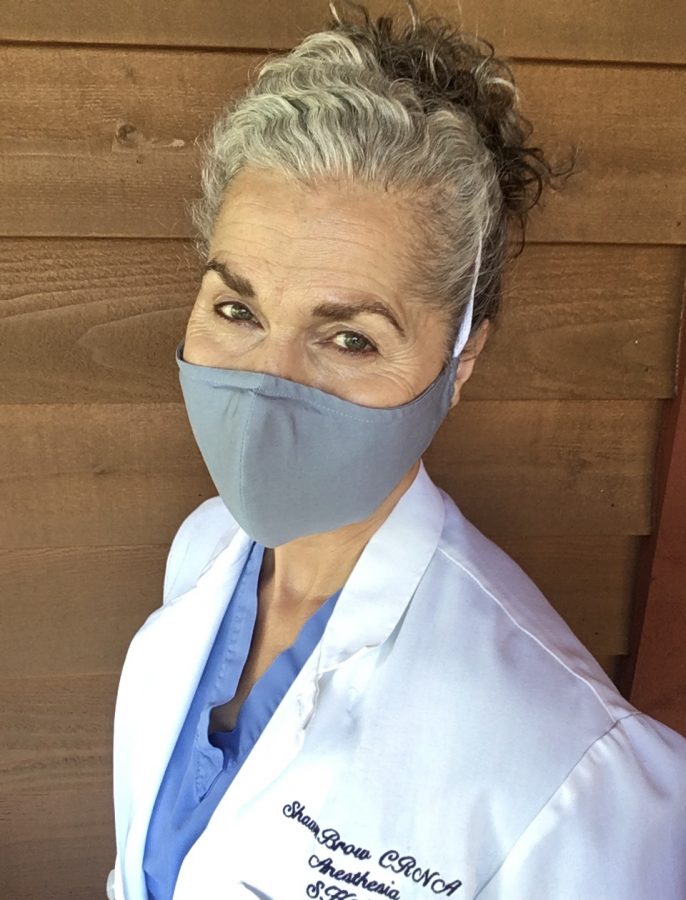

Shawn Brow, nurse anesthetist in Spokane and adjunct faculty with the Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine, wears a mask that she and her team designed.

July 17, 2020

Members of WSU faculty designed and tested facial coverings to see if they can be used by healthcare professionals as a last resort.

Early in the pandemic, the team heard there was going to be a shortage of N95 masks. They wanted to design a mask a healthcare provider might use if they lacked sufficient personal protective equipment, said Marian Wilson, assistant professor in the College of Nursing in Spokane.

The team also wanted to see if they could make a mask the public could use and be confident about its level of protection, Wilson said.

“We wanted to test it just to see how close we could come to getting the level of protection that you would get from a N95 mask,” she said.

The team is composed of Wilson, Roschelle Fritz, WSU Vancouver College of Nursing assistant professor; Shawn Brow, nurse anesthetist in Spokane and adjunct faculty with the Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine; and Georgette Thornton, a professional dressmaker by trade.

Wilson, Fritz and Brow started reading scientific literature to see what people were suggesting internationally, Wilson said.

They tested two masks. One was designed by Brow and Thornton. The other was an eight-layer cotton mask they created based on compiled information from Asia, Fritz said.

Fritz said she conducted the study of both masks at the Arbor Health, Morton Hospital by fit testing, which are tests conducted by hospitals to ensure N95 masks fit people’s faces. The study’s participants were front-line staff who might be asked to go into an airborne isolation room.

The fit testing process involves putting on hoods that completely cover participants’ heads and faces. Inside the hoods, an aerosolized sweet solution is sprayed about 10 times to test the participants’ sensitivity level to the solution, she said.

Participants check to see if they can smell or taste the solution. If they cannot, the solution is sprayed in rounds of 10 until the participant can smell or taste it, she said.

Afterward, participants go through several activities while the solution is sprayed, such as moving their head from side to side, breathing deeply, marching in place and reading a paragraph of text, Fritz said.

These activities simulate actions, like bending over, that workers normally do in a patient’s room, she said. During testing, they did not want the seal of the mask to break.

With the double-filter mask Brow and Thornton designed, 12 of the 28 participants never smelled or tasted the solution. Four of the 12 participants who passed the test did not tape their masks. If the double-filter mask failed the test without taping, the participants taped it. Eight of the 12 passed the test when they taped their masks.

“The main finding is that we were able to have anyone pass at all because really, we would not have expected that we could simulate the fit of an N95 mask with something that we made from home,” Wilson said.

Fritz said she thinks the number of people who passed the fit test would have been higher if they had started robust taping on the first day of testing.

Fritz said she does not claim the mask Shawn and Thornton designed would protect someone from coronavirus. However, the mask shows potential, especially with robust taping, as an alternative to an N95 mask if and only if there is a severe shortage of N95 masks and PPE. The mask could be considered a stopgap if that happens, but only with caution.

The eight-layer cotton mask that was created based on a compilation of information from Asia was only tested when the participants taped their masks because Fritz said she thought the mask might fail based on the data. It did fail.

The study was funded with $8,000 from the WSU Vancouver Office of Research, she said.

Thornton, one of Brow’s yoga therapy students, came to Brow after she received an email from Days for Girls, an organization that makes reusable, washable feminine hygiene products and distributes them to girls and women worldwide. The email stated the organization would take part in sewing masks for the public, Thornton said.

“I just didn’t want to be making everyday masks that I knew would not be sufficient for healthcare workers,” Thornton said. “I wanted to do something that would benefit the healthcare workers and their lack of PPE.”

Thornton and Brow designed masks that are made of high-quality cotton with a pocket for a 3M filter that can easily be removed and replaced, Brow said. The ties used in the mask come up over the head and make the mask fit tightly. Brow said she washes and reuses her filter, but she said the team is not sure how that affects the effectiveness of the mask.

“That would be another step of studying,” she said. “Washing the filter, does it have any change in the effect of filtration efficiency versus just putting a new one in each time?”

Thornton said she is mailing a mask pattern to people who want one, and she is also making masks for people. Those interested can reach her at [email protected].

Thornton said she asks for a $10-15 donation to Days for Girls for those ordering a pattern. She asks for a $15-20 donation for each mask ordered.