WSU tree researchers attempt to prevent Little Cherry Disease

Pathogens are spread between trees by leafhopper insects; white clay could deter insects

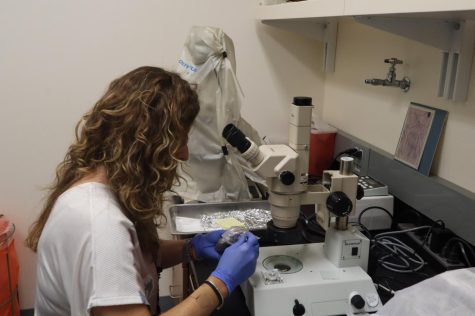

Scott Harper, WSU assistant professor of virology, examines diseased cherries, which can be small and bitter.

August 28, 2020

WSU scientists and cherry growers are finding new ways to prevent Little Cherry Disease, an infection that spreads between trees and can significantly decrease fruit yield.

When a tree growing fruit with pits, such as cherries or peaches, is infected with the disease, the only known way to keep it from spreading to others is to remove the entire tree, said Scott Harper, assistant professor of virology at WSU’s Prosser Extension Center.

“It’s not a simple spray and it’s going to go away, problem solved,” Harper said. “This is a much more complex disease system that’s going to take a lot longer to manage.”

The disease was a problem in the Pacific Northwest in the 1940s and 1950s, but appeared again in 2018. A Little Cherry Disease Task Force was formed after the disease resurfaced. One of the task force’s goals is to find disease solutions that do not require the destruction of whole orchards.

An infected tree may have clusters of fruit that are smaller or less ripe than neighboring ones, said Per McCord, associate professor of stone fruit breeding and genetics at WSU’s Prosser Extension Center.

Fruit from an infected tree may not taste as sweet as it should and cannot be sold, McCord said.

The infection starts in a few clusters of fruit and will eventually spread to other branches and the rest of the tree until the whole thing has to be removed, Harper said.

“It’s a very slow disease—it’s very easy to miss in the early stages,” Harper said. “And that’s probably one of the reasons it accumulates, because people are missing it early.”

Little Cherry Disease can be caused by several pathogens, McCord said. Little cherry virus 1, little cherry virus 2 and a bacterium called X-disease phytoplasma can all cause symptoms in trees.

Leafhoppers, small insects that feed on sap, can spread X-disease phytoplasma between trees, said Tobin Northfield, chair of the task force and assistant professor of entomology at WSU’s Wenatchee Extension Center.

When a leafhopper eats sap from an infected cherry tree, it spreads phytoplasma to the next tree it feeds at, continuing the chain of infection, he said. Leafhoppers can spread the pathogen long distances, potentially causing infection in neighboring orchards.

Researchers are testing kaolin clay, a non-toxic white mineral powder, to deter leafhoppers, Northfield said. When sprayed on trees, it acts like camouflage. Using white plastic ground cover in orchards is another possible deterrent.

A long-term solution could be breeding trees that are resistant to Little Cherry Disease, Harper said.

To do this, breeders would need to identify desirable characteristics, including disease resistance, in fruit and trees and find trees that exhibit them, McCord said.

“[Then it’s] crossing the best with the best and hoping for the best,” he said.

![“[The heat] really has an effect on how much we have available to meet orders every week.](https://dailyevergreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_0565-2-475x316.jpg)