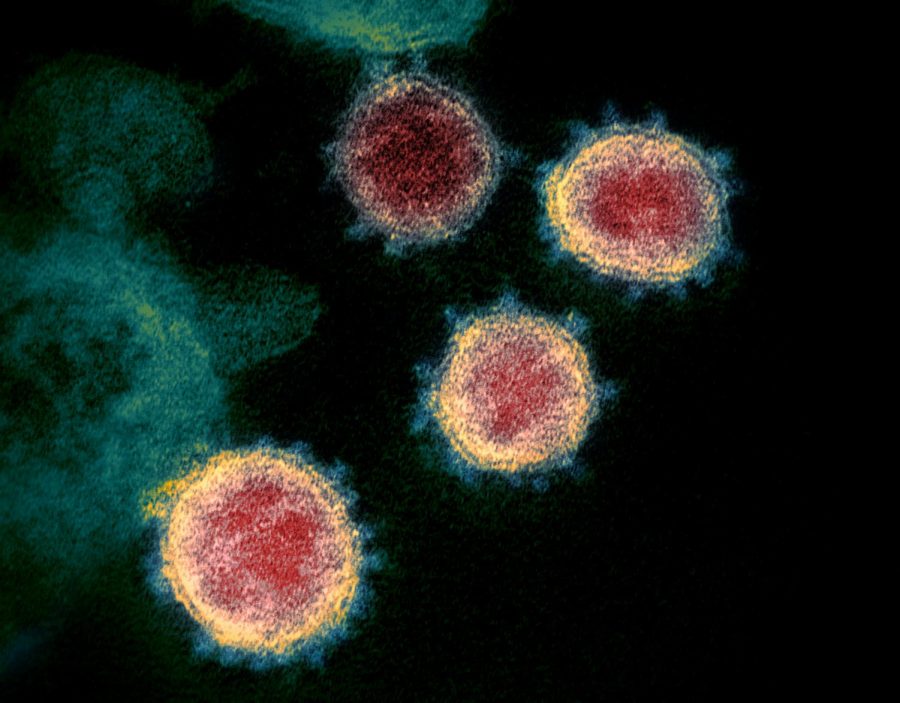

OPINION: Coronavirus control is a lot harder than we think

Vaccine responses, trials, are taking longer than we initially assumed

Testing and vaccinating for the coronavirus is proving significantly more difficult than we thought.

October 7, 2020

An era of misinformation has led to the rejection of science and verifiable information, although this has proven to have visible cause and effect by the transmission of what we know as the coronavirus.

March 13 was a day that provoked fear among millions of Americans, while the days leading up to it were filled with denial for others. The day the coronavirus shut down the country was the day millions lost employment, and thousands were already infected.

There was little understanding as to why a virus some referred to as “flu-like” would have such an impact in such a short amount of time. After nearly 10 months of examining all known facets of COVID-19, vaccine development in many countries has reached the stage of human clinical trials. As many worry that the process may have been hurried, scientists assure that aggressive research and modern vaccine technology could alleviate the momentum of COVID-19.

When this strain of the virus emerged, scientists worldwide began their research immediately, searching for the cause and racing to find a preventative vaccine for the zoonotic virus. For clarification, the cause of a zoonotic virus or disease involves the transmission of pathogens between animals and people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In this case, the new disease was promptly identified as a novel beta-coronavirus related to SARS-CoV and other bat-borne coronaviruses.

The virus demonstrated its intensity through rapid transmission from its origin to the entirety of one of the most populous countries in the world. In efforts to slow the outbreak, the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 International Health Regulations Emergency Committee urged countries to implement robust guidelines that involved detecting the virus, isolating, contact tracing and social-distancing.

Prior to developing a diagnostic test for the virus, individuals were encouraged to stay home and only leave the house if they were essential workers or needed supplies. The reason for the lockdown was to slow the spread of the virus, while there was not yet a known diagnostic test or a feasible treatment for COVID-19 patients. It was also intended to avoid overwhelming medical facilities that had a critically low supply of ventilators and personal protective equipment for medical staff.

Once a diagnostic test for COVID-19 was developed by the CDC, the established objective was to simultaneously detect influenza viruses A, B and SARS-CoV-2. This was perceived as an endeavor to allow medical facilities to conserve their resources and surveillance the rate of influenza and COVID-19.

Nevertheless, oversight led to some false positives due to the presence of a specific chemical reagent in the test that has since been eliminated. The absence of the reagent would not alter the efficacy of the test, according to the nature of the FDA-permitted test. Many individuals used this error as a reason to discredit the validity of the CDC when the virus itself has been an evolving matter since the first case emerged.

“Since January, the scientific community has been focused on vaccine research. Within the first month of research, there were already 200 vaccine candidates,” said Michael Letko, molecular virologist and assistant professor in WSU’s Paul G. Allen School for Global Animal Health.

Letko said existing vaccine technologies like the Moderna Vaccine are built to warrant a quick response to new pathogens and guarantee that it would be safe when applying vaccines to a different virus. Basically, if the general safety profile is developed for one vaccine, it is much easier to apply it to another virus.

The fact the virus has resulted in a global pandemic justifies the urgency scientists have when approaching this research. Driven by necessity and the absence of a grace period, researchers are trying to accelerate the process of finding a viable vaccine, but it is not at a totally unusual pace, Letko said.

“Especially now, we see on the news groups saying they want a vaccine ready by a certain date. [It creates] a sense that this research is being rushed,” Letko said. “However, [the process of research] is moving very quickly, but it does open this up for mistakes or other potential issues.”

Letko said each vaccine candidate will have its own potential side effects, and it is all dependent upon what is in the shot. When giving any kind of medicine to large groups of people, their genetic backgrounds vary so the vaccine’s behavior is much less predictable, but this again is the reason why human clinical trials with 100,000 participants exist; this allows researchers to observe the interactions of the vaccine with a largely diverse group of people.

In terms of the timeline, Letko predicts that around this time next year, enough people will receive the vaccine once it has been released, but it is nonetheless a long road. Still, when a viable vaccine has been released, it will be another long process to go from finding a well-functioning vaccine to producing enough doses to distribute to the population, which that in itself takes months, Letko said.

Concerning the claims of a vaccine being ready by Nov. 1, there may be good data that points toward a better vaccine candidate to concentrate on, but by no means will there be 100 million doses ready to go by that date, Letko said.

There may be some speculation regarding whether an evolved strain of COVID-19 could foster a potential threat after the development of a vaccine. Having dedicated his research to coronaviruses, he said one of the factors of coronaviruses is their ability or inability to mutate. There is always a concern with viruses changing over time, but this virus will not exhibit mutations that one would expect from influenza.

In the matter of frequency of vaccination, this may not be a vaccine individuals will need to consistently get updated because the virus is mutating, but because it is possibly a poorly engineered vaccine, or there is a decline in immunity, Letko said. Although this fact exists, there are variants of the virus examined to be more easily spread and more pathogenic, Letko said. However, those mutations would not interfere with the efficacy of a vaccine. Thus, any mutation of SARS-CoV-2 is to be monitored but would not prevent a vaccine from functioning to its fullest capacity, Letko said.

Regarding future research, there will definitely be continual studies of COVID-19 “until the end of time” because this virus has proven just how impactful it can be, Letko said. Every single mutation will be closely observed by at least 200 scientists.

Learning about immune responses and investing more in the pathology of the virus could possibly lead to a short-term improvement in the mortality rates, said Letko. But the research Letko has contributed to, regarding tracing viruses back to their animal reservoirs and examining which viruses are zoonotic, is information that can help prevent future breakouts of zoonotic diseases from occurring in the long- term.

“Of course I will get the vaccine because I feel as if it’s my moral responsibility to contribute to herd immunity and global human health,” said Jonah Wisen, WSU student and College of Agricultural, Human, and Natural Resource Sciences ambassador. “I have no grounds to refute experts that have spent their lives studying and preparing for this exact moment by refusing to get a vaccine.”

The same question lies upon the rest of us — will we make contributions towards controlling this pandemic, or will we continue to question the experts?