Bacterial compound may treat entire class of parasites

Apicomplexans cause symptoms in humans, animals; drug testing process will take years

Roberta O’Connor, associate professor in WSU’s Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology, extracts shipworms from wood in the Philippines. Shipworms contain bacteria that produce useful compounds for drugs.

July 3, 2020

A compound produced by bacteria in shipworms may help WSU researchers create a drug treatment for a class of parasites called apicomplexans.

“This is the only drug we know of that targets this whole class of parasites,” said Roberta O’Connor, associate professor in WSU’s Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology.

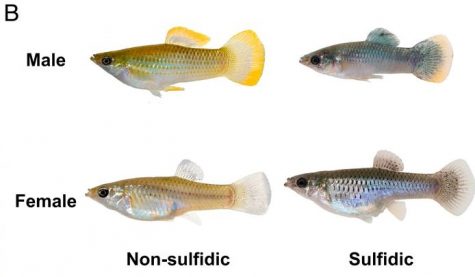

Cryptosporidiosis, malaria, toxoplasmosis, theileriosis and babesiosis are all diseases caused by apicomplexan parasites. They can cause symptoms in both humans and animals, O’Connor said.

Cryptosporidium is the second leading cause of diarrhea in children under five, O’Connor said. It is endemic in many developing countries, but outbreaks are becoming more common in the U.S. when water treatment systems fail.

“When people look for it, they find it,” she said. “They just don’t often look for it.”

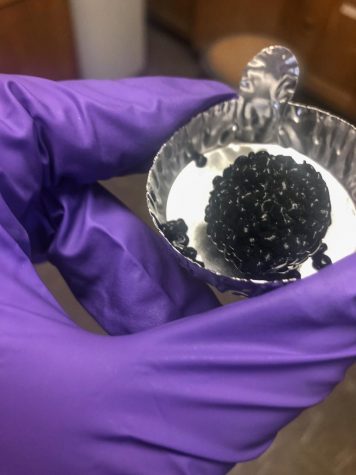

Shipworms, marine mollusks that feed on wood, have bacteria in their gills that produce enzymes to help them digest wood. O’Connor said she grew two types of shipworm bacteria to see what they produced. In the second type, she isolated tartrolon E, a compound that effectively killed apicomplexans.

“We were completely floored,” O’Connor said.

Apicomplexans are difficult to treat because they often develop resistance to drugs, she said. There are very few effective treatments for these parasites and they may be less effective as the parasites become resistant.

“We have not been able to generate resistance in the lab [to tartrolon E],” O’Connor said.

In order to test the effectiveness of tartrolon E, O’Connor said she first infected host cell cultures with the different types of parasites. Then she treated the cells with different dilutions of the compound to determine how much is needed to effectively kill half of the parasites.

“We always make sure that we’ve established the infection, because what we want are drugs that actually kill the parasite when it’s inside the host cell,” O’Connor said. “The drug needs to make its way into the host cell to kill the parasite.”

The parasites are grown with luminescent tags, so cell cultures that are infected will glow more brightly than ones that have been effectively treated with a parasite-killing compound, she said.

O’Connor has a five-year grant to test and develop tartrolon E as a drug. This process will involve testing the compound on infected mice and newborn lambs to determine how it moves through different systems in the body and if there are any toxic side effects, she said.

“We need to define what … is a safe and effective dose and dosage regimen,” said Nicolas Villarino, assistant professor in WSU’s Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences.

It may take years before the drug becomes available for use in humans because of the extensive testing process that is required, Villarino said.

Once researchers are able to determine a safe and effective dose for mice and lambs, they need to be able to predict proper dosages for other species, he said.