Kill or be Killed

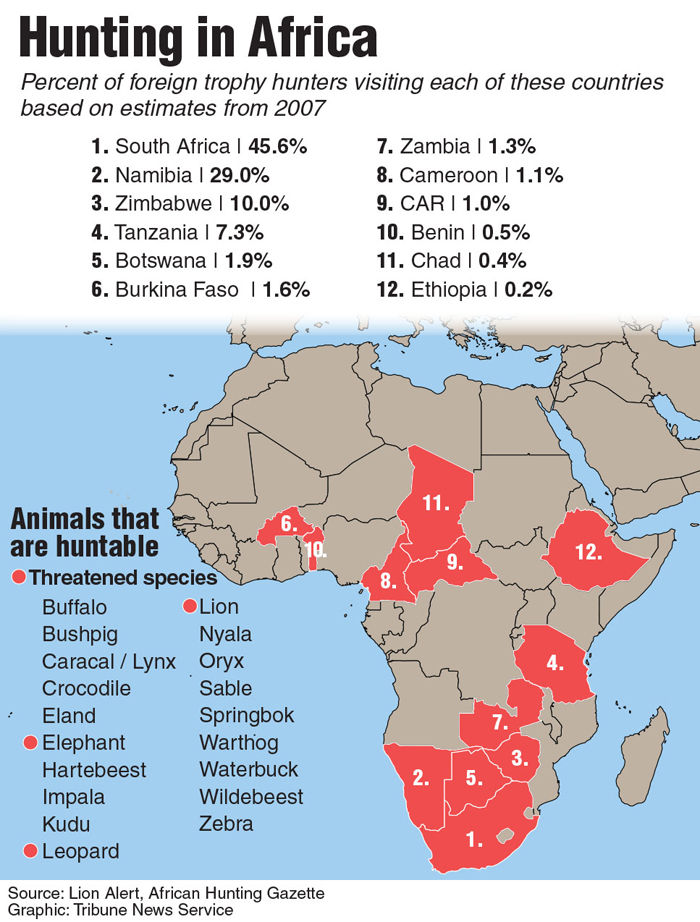

Top trophy hunting countries in Africa based on proportion of hunters visiting. Regulating animal populations through trophy hunting is necessary for the well-being of human lives.

September 24, 2015

Kill or be killed: that’s the reality for many families in villages in the African country of Botswana in the two years following the illegalization of trophy hunting.

Animals such as lions and elephants have been allowed to run rampant, taking their toll on the livelihood of some of the poorest communities on the continent.

While trophy hunting has recently come under fire, when the absence of hunters means human lives are threatened and negatively affected, the law must be reconsidered.

Human lives being threatened due to the illegalization of trophy hunting is unacceptable.

The New York Times published an article addressing these rising problems among African villages.

Not only has this exponential rise in big game animals led to the decreased ability to successfully cultivate crops such as watermelon, maize and beans, they also threaten health clinics, homes and schools. In underdeveloped countries, these effects are detrimental.

Similarly, economies in countries such as Botswana – which previously mostly relied on wealthy foreign hunters being chartered on hunts in villages throughout the country – have been severely broken.

These hunts are not cheap, many times costing $30,000 – $100,000 per hunt. Money that was used to install amenities such as toilets and plumbing and provide schools for children is no longer available.

The call to end trophy hunting largely stems from conceived Western ideas of wild animals, ideas which come from movies such as The Lion King and The Jungle Book. We are raised into thinking that these animals are cuddly and friendly when in reality they are raging carnivores which humans stand little chance against.

An article published by National Geographic in 2007 cited that over time, if properly managed, trophy hunting can aid the conservation efforts of African wildlife.

Though this may initially seem like a paradox, the legalization of regulated hunting can decrease the amount of poaching hunters within national parks, according to biologists.

Additionally, money and taxes produced from trophy hunting is available to be pumped back into conservation efforts by expanding national parks and raising the awareness of poaching.

Zoe L. Hanley, a Ph.D student in the Large Carnivore Conservation Lab at WSU, brought up a contradicting opinion from the point of view of a biologist.

Though admitting that WSU does not have any specialized personnel in the topic of trophy hunting in Africa, she referred to multiple scientific journal articles addressing the detrimental effects of trophy hunting.

These articles displayed how trophy hunting has only led to a major decline of populations of large game.

Though it seems biological evidence is split, and many conservationists will be critical of any sort of legal trophy hunting, the human element must be taken into consideration. Ultimately, a solution must be derived to both conserve these animals as well as sustain the well-being of human life.

Philip Grossenbacher is a sophomore studying english education from Lynwood. He can be contacted at 335-2290 or by [email protected]. The opinions expressed in this Column are not necessarily those of the staff of The Daily Evergreen or those of The Office of Student Media.