WSU researcher fights harmful pathogen in carrot seeds

Pathogen that produces ingredient commonly found in ice cream is damaging carrot crops

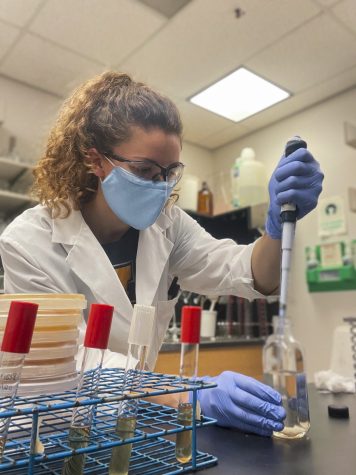

COURTESY OF CAHNRS COMMUNICATIONS

A team of researchers is studying different treatments to kill the bacteria that causes a disease in carrot seeds. The disease is not harmful to people who eat the crop, but carrots cannot produce enough nutrients if they are infected with it.

February 4, 2021

A WSU researcher and a university alumnus are working on a team to prevent the growth of a bacterial pathogen in carrot seed crops.

Bacterial blight is a seed-borne disease in carrots that is prevalent worldwide, said Jeremiah Dung, WSU alumnus, project director and associate professor at Oregon State University. When carrots are affected by bacterial blight, their leaves are spotted with discoloration.

The bacterium infects the carrot, starts to grow on the leaf’s surface and multiplies rapidly, said Lindsey du Toit, professor and extension specialist in WSU’s Department of Plant Pathology.

“You end up with millions of bacteria per gram of leaf tissue,” du Toit said.

The bacterium breaks down the cells inside the leaf, killing the tissue, she said. The infected leaves cannot photosynthesize well, so the carrot cannot produce enough nutrients, which the crop needs to grow roots.

The lack of nutrients also creates a problem for the leaves, du Toit said.

“The leaves are not as effective at photosynthesizing and moving food into the roots,” du Toit said.

Many carrots are harvested by pulling them up by their leaves, she said. The bacteria make the leaves brittle, so it is harder to harvest the carrots properly.

The largest concern with the leaf blight bacterium is the difficulty in producing a healthy, good-sized carrot, du Toit said.

The research team she leads at WSU analyzed organic and conventional pesticides sprayed on crops to see how effective they are at killing the pathogen, she said. They also monitored the spread of the pathogen in carrot seed crops throughout their growth cycle.

Researchers found that putting the seeds in hot water can help kill the bacteria while keeping the seed alive, du Toit said. However, it is more difficult when the infection is deep, and there is a higher risk of killing the seed.

With funding from the USDA Specialty Crop Research Initiative, du Toit is now working with Dung to look at different ways the carrot seeds can be treated on a microscopic level, she said. The team is six months into a four-year-long project.

They have started to research different treatments, including exposing the seeds to UV light and applying viruses to kill the bacteria in the infected seeds, Dung said.

Washington and Oregon produce 75 percent of the world’s carrot seed, du Toit said.

The seed companies that test the carrots for pathogens determine if they can be sold or not, depending on how much a carrot seed is infected, she said. Infected seeds may mean the grower is paid less or nothing at all.

The pathogen is not harmful to people, even if they eat a carrot infected by the disease, du Toit said. It produces xanthan gum, an ingredient that can be found in chewing gum, ice cream and toothpaste.

“This pathogen is a pathogen of carrots, not a pathogen of humans,” du Toit said.