Researchers to reduce wine’s alcohol content

Yeast found on grapes impacts quality, profits

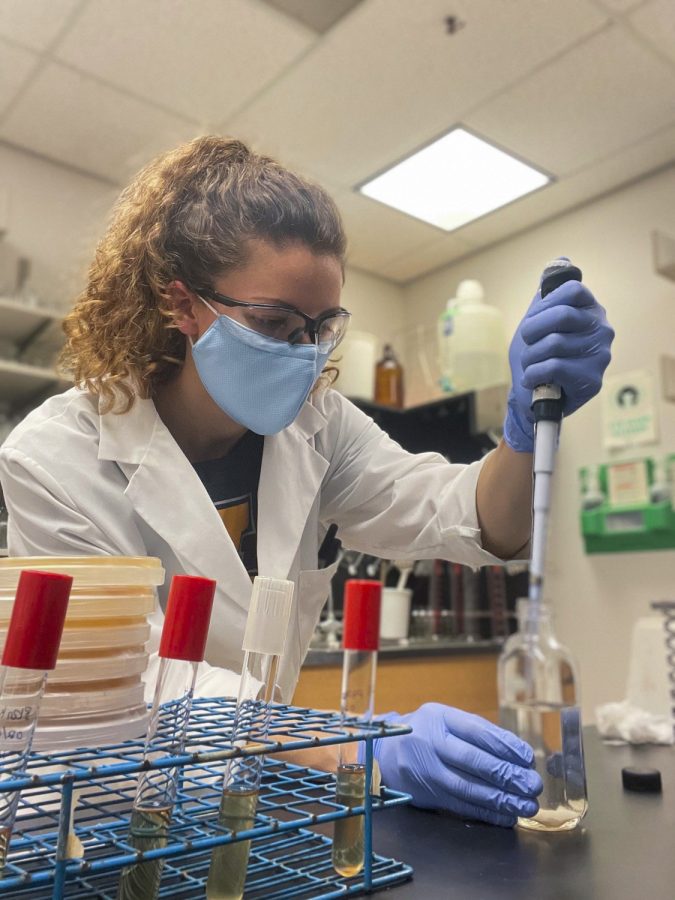

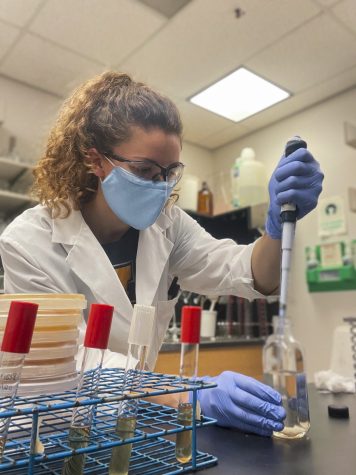

COURTESY OF HEATHER CARBON | FILE

Food science graduate student Heather Carbon collects a fermented sample of synthetic grape juice made from wild yeasts.

February 11, 2021

WSU researchers are looking to improve the fermentation process for Washington winemakers, who are part of an industry worth about $8.4 billion.

The team, made up of undergraduate and graduate students, wants to identify ways yeast can reduce alcohol content in wine, said Heather Carbon, WSU food science graduate student.

Saccharomyces, a group of yeasts typically used in the winemaking process, normally ferment grapes by consuming their sugars to produce alcohol and carbon dioxide, Carbon said.

However, if grapes are harvested with higher sugar levels than normal, the wine could ultimately contain a higher alcohol percentage, she said.

“This could make your wine taste very bitter and have a strong alcohol taste,” Carbon said. “It could ruin the sensory aspects of your wine.”

Higher sugar levels could also lead to an incomplete fermentation, which leaves residual sugar in the wine that other microorganisms could consume, potentially altering the taste of wine, she said.

These higher sugar levels could also result in potentially higher taxes for the winemaker, she said.

In a 2015 study conducted at a Tri-Cities vineyard, WSU professor and project lead Charles Edwards said he helped discover 55 species of non-Saccharomyces yeast, which naturally occur on the skins of grapes used in wines.

Carbon said the study found the native yeast species produce byproducts that affect the flavor and outcome of the wine. Winemakers harvest the grapes, bring them into the winery and start the fermentation process with added Saccharomyces while the native yeast species have already begun their own fermentative activity.

This extra fermenting also causes the wine to have a higher alcohol content, she said.

The current WSU research started about six years ago and builds off the previous wine study, Carbon said. It dives deeper into learning how to control the yeast and fermentation process to create wine that tastes better and is more financially profitable for winemakers.

She said winemakers commonly use grapes with high sugar content because of harvesting practices. This leads to consumers finding wines with 15 percent alcohol on the shelves rather than the preferred 13 percent.

“Not only do you have different types of grapes that you can use or different processing methods, but you also have a whole world of microbiology you have to consider in a fermentation process,” Carbon said.

Students grow the wild non-Saccharomyces yeasts in a Pullman-based lab. Currently, the group is studying how the yeasts behave in different temperatures using synthetic grape juice instead of real grape juice to ensure sterility and controlled conditions, Carbon said.

A full fermentation could take days to weeks, depending on the environmental conditions and type of yeast, she said.

Edwards collaborates with local winemakers to collect input for the study because the researchers are not experts in the selling of wine. One such winemaker is Brian Carter, owner of Brian Carter Cellars in Woodinville, Washington.

“He helps guide some ideas from the commercial and the industry perspective,” Edwards said. “It has really helped us to hone our research, and to help us to define the direction.”

Edwards said the project is funded by WSU, the Washington State Wine Commission and the Auction of Washington Wines. The two wine organizations expressed interest in ways winemakers could differentiate the quality of their products using various yeast strains.

“The end goal is to provide winemakers with another tool in their toolbox to differentiate their products,” he said.